Jasprit Bumrah is the third Indian bowler — after Harbhajan Singh against Australia in 2001 and Irfan Pathan against Pakistan in 2006 — to take a hat-trick in Tests. (Photo: BCCI)

Thank you for reading this post, don't forget to subscribe!Shared News| Updated: September 2, 2019 9:16:37 am

Among modern-age bowlers, no one perfected the art of taking hat-tricks like Wasim Akram — the Pakistani maestro nabbed four, two apiece in Tests and ODIs. Nine of the 12 victims were blasted out in a predictably Akram-esque manner. Bowled. Six of them perished to his signature in-swingers, ripping, devilishly late-swerving corkers, beating batsmen by both pace and movement. Almost frighteningly predictable.

The faces of befuddled batsmen tell a story — they knew the unpreventable eventuality. It’s not that they weren’t aware of the most shining weapon in Akram’s armoury, but it was irresistibly unpreventable. Like death and taxes in life, or the hurricanes in the Caribbean Sea.

Like it’s with Jasprit Bumrah these days. In these technologically-intoxicated days, it’s not difficult to gather data, dissect and dissemble a bowler, strip him to his elements, however unique or skilled he is, and devise counter-measures. Even before you’re in the middle, you can visualise and draw trajectories of the delivery in your mind, condition your reflexes, toughen your mind and bound into the middle. Soon, there could be batting cages that can simulate the actual game scenario. But there’s only so much technology, or for that matter gathered wisdom or human will, that can help you against great bowlers when you’re facing them out in the middle. It’s their predictability that makes them more indecipherable, that infuses a mortal dread, that makes batsmen helpless.

Bumrah took six wickets in the first innings as India bowled out the West Indies for 117 to take a 299-run lead. His 6-27 included a hat-trick, only the third by an Indian in Test cricket (after Harbhajan Singh in 2001 and Irfan Pathan in 2006).

The faces of Bumrah’s dazed hat-trick victims reveal the story. Darren Bravo first. He knew exactly how Bumrah would bowl. He would look to slant the ball across him, probing his outside edge — the classical right-arm fast bowler’s ploy from over the stumps. So even before Bumrah exploded into his action, Bravo is shuffling across to cover his off-stump, get outside the line and leave the delivery to safety. Only that he can’t, he hangs his bat frozen outside the off-stump, sees the ball landing on middle-stump and swinging away. Bravo doesn’t know how much it would swing. He has to make a judgment in a split second, or even less when facing Bumrah. And he plonks his bat, praying the ball would miss his bat. It doesn’t. The helplessness flickers in his eyes.

Enters Shamarh Brooks. Even before he marked his guard, those that have watched Bumrah in the last few years knew the impending delivery. A sense of deja vu, if you may. A full, sharp in-swinger on middle-and-off, which the batsmen would consider ghastly fortunate to inside-edge. Brooks didn’t. He stood still, determined to make his move at the very last moment. But before he could bring his bat down, the ball had cannoned off to his fresh white pads, leaving a tattoo-like mark on them. That would, in time, serve a reminder of Bumrah’s in-swing mastery. Bumrah, it seems, hurries time, as much as stops it.

Next was Roston Chase’s turn. Among all West Indies batsmen, he seems the sturdiest in defensive technique. He seems to have time, a cool disposition and ability to judge lengths. But he, like his colleagues, couldn’t resist Bumrah’s fury on a draining, humid afternoon. He’s smart enough to second-guess Bumrah’s intentions. Most bowlers, especially fast bowlers on a hat-trick, look to repeat the same delivery that had put them on the brink of the accomplishment. So Chase’s mind might have been running a reel of Bumrah’s in-swinger on loop. Just need to bring the bat down in time, he might have steeled his mind, to manage at least the thinnest fragment of wood on the ball.

The sequence plays out exactly the same way as anticipated. So thinks Bumrah, So thinks umpire Paul Reiffel. Only that Chase hadn’t, as the pad had obstructed his bat from coming down fully. The front foot went slightly across than he might have designed it to. Against Bumrah, such minutest of mistakes won’t go unpunished. Again, like his colleagues, Chase knew Bumrah’s intentions, yet doom was unpreventable.

In fact, five of his six victims perished to in-swingers, just as all five of his scalps in the second innings in Antigua were wrought by out-swingers. It boggles the mind how repetitiveness can be so successful. The same bowler performing the same tricks with the same amount of success.

It’s the case with all greatest sportsmen. They keep doing the same stuff, day in and day out, only that they do it with more virtuosity, perfection and conviction to pull it off at any given moment, than the merely good ones. How many times has one seen Bumrah just striding into his run-up without even warming up and just blasting the stumps or pads? In the World Cup, it was such a commonplace sight that he made one wonder whether he was a bowling robot. Or in other words, it’s greatness repeating itself.

It’s the same with Lionel Messi — a bulk of his 419 goals have come in a similar manner. A breezy run, a hoodwinking dribble and a neat swish of that left foot that sends the ball spinning through its orbit to the top corner of the far post. Messi, the maestro he is, has scored goals in every manner humanly possible. But it’s the sequence that would remain as the indelible image of his career.

Or take Roger Federer, no player in tennis history had such ludicrous command over a range of strokes, but it’s the silken forehand that defines him, that brushstroke of a whip, evading the opponent’s reach by a fraction, whistling right under his nose to eternity.

Closer to Bumrah’s game, Shane Warne, the master of bluff, preyed most of his 708 wickets with leg-breaks. So have James Anderson’s in-swingers. Like all of them, Bumrah has a bagful of tricks, but it’s the in-swinger on which he has imprinted his signature. It’s predictable, yet unpreventable.

It shone in the eyes of the fans at Sabina Park. It wasn’t antagonism that lit their eyes but admiration, a blessed feeling that they are watching greatness unfold in front of them. A suspension of belief. Not to have been beaten, but to have been there, watching Bumrah wreak havoc, in a predictable yet frighteningly unpreventable way.

Bumrah and the beauty of predictability

Five of Bumrah’s six victims in Kingston perished to in-swingers, just as all five of his scalps in the second innings in Antigua were wrought by out-swingers. The dismissals of Shamarh Brook and Roston Chase show how helpless batsmen can be while facing Bumrah.

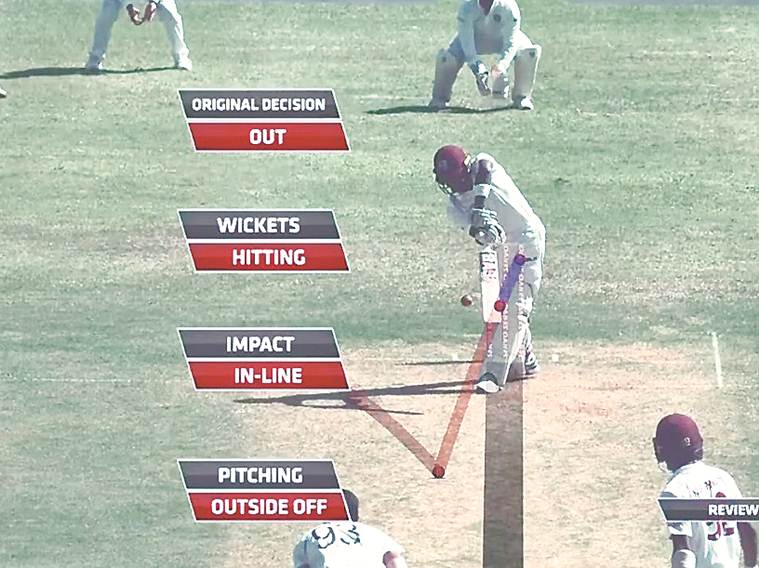

Screenshots showing how Bumrah trapped Brooks.

To Brooks, Bumrah bowled a full, sharp in-swinger on middle-and-off, which batsmen would consider ghastly fortunate to inside-edge. Brooks didn’t. He stood still, determined to make his move at the very last moment. But before he could bring his bat down, the ball had cannoned off to his fresh white pads.

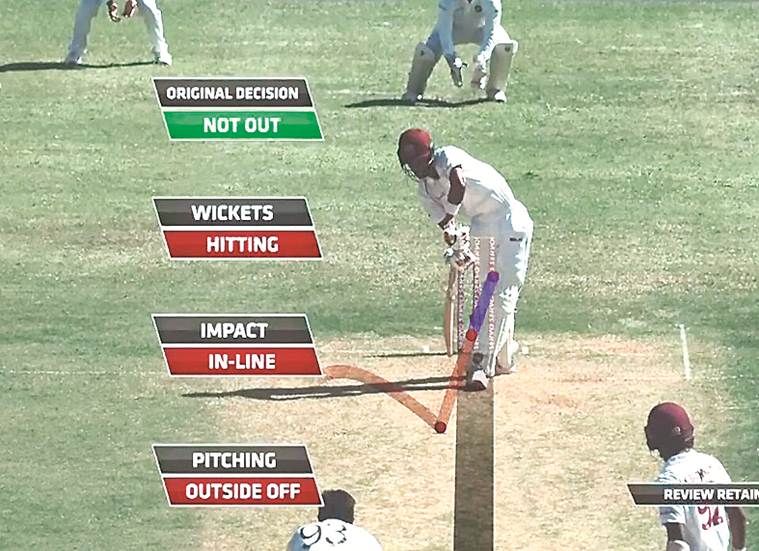

Screenshots showing how Bumrah trapped Chase.

Roston Chase is smart enough to second-guess Bumrah’s intentions. Most bowlers on a hat-trick look to repeat the same delivery that had put them on the brink of the accomplishment. So Chase’s mind might have been running a reel of Bumrah’s in-swinger on loop. Just need to bring the bat down in time. Chase tried, but the pad obstructed his bat from coming down fully. The front foot went slightly across than he might have intended. Like his colleagues, Chase knew Bumrah’s intentions, yet doom was unpreventable.