Sandeep Dwivedi grew up in a house that overlooked the ground where an 8-year old Cheteshwar Pujara learnt to bat from his cricket-tragic father. He witnessed the baby steps taken by India’s No.3, closely followed his rise up the ranks and has watched him bat around the world.

Thank you for reading this post, don't forget to subscribe!Shared News| January 25, 2020 9:28:12 am

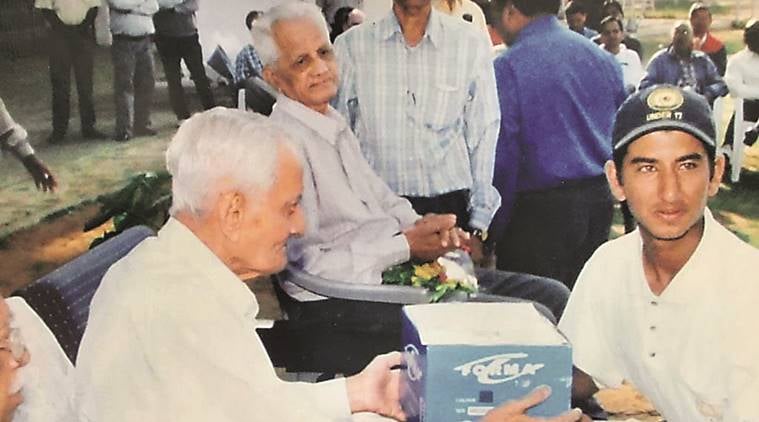

Pujara turns 32: The man who is now a towering figure in India’s Test batting lineup was called Chintu or ‘Pujarabhai no chokro’, the latter was popular with his father Arvind’s colleagues from the Engineering department. (AP Photo)

I grew up in a home that overlooked an unfenced local cricket ground that occasionally hosted first-class games. 3, Kothi Compound, Rajkot was a much-envied address among all Railway Colony kids. Our terrace towered over the sightscreen to give the much-valued behind-the-bowlers’ arm vantage point to watch cricket. The front gate opened straight into this all-purpose Railway ground where we played tennis ball cricket, learnt to cycle, flew kites, made friends, had fallouts and primarily spent countless idle afternoons venerating mostly mediocre club cricketers.

That wonderland of our teenage years, the graveyard of our charmingly unrealistic sporting dreams, was also where the seeds of Indian cricket’s most recent, most elusive win were sown. The hero of the Test series win that took 71 years and 11 tours in the coming is from our neck of the woods.

The Man of the Series in India’s first-ever Test triumph in Australia, celebrated as much for his 521 runs as for the 1,258 balls he faced, first hit a hard red cherry in a corner of our ground, a strong hard throw distance from my home. Cheteshwar Pujara once upon a time lived in our colony and the cricketing Waterloo enforced by India, traces its origins to the playing field of our childhood.

I saw the making of Cheteshwar.

Cheteshwar was barely 8 when his father Arvind dressed him up in sparkling whites, made him wear home-made mini pads and got him to the Railway ground. He had light eyes and an angelic face.

The Instagram generation was finding Pujara lit. Over-fed with T20 cricket, where they tried to find their batting heroes, they were now understanding the science of Test match batting.

Everyone called him Chintu or ‘Pujarabhai no chokro‘, the latter was popular with Arvind’s colleagues from the Engineering department. He was too tiny for a net session but his cricket-mad father, a Ranji Trophy wicket-keeper batsman and sports quota Railways employee, wanted an early cricket christening for his son.

Ask any Kothi Compound resident of late 90s to early 2000 and they would remember seeing the Pujaras on most evenings in the corner of the Railways ground, under the neem tree, next to the volleyball court. The father rolling the ball along the ground, the son methodically bringing the bat down and playing it straight back to him.

Years later, Arvindbhai would tell me why he avoided giving the usual one-bounce throw downs to his pre-teen son. “At that age, kids swing their bat wildly to connect to the ball and end up playing cross-batted shots. I didn’t want Chintu to develop that bad habit.” The ball that Arvind set rolling wouldn’t stop, it travelled around the world. Chintu would never forget the first lesson he got under the neem tree, he would continue playing straight, complete 5,000 plus Test runs at 30 and get counted among the last few batsmen responsible for keeping the dying art of Test match batting, alive.

After his third hundred in Australia, the cricket universe stood up in ovation. The batting deity Viv Richards called his batting “pure gold”, the brutally blunt, hard-to-please Kevin Pietersen tweeted: The RESPECT you get as a cricketer for what @cheteshwar1 is doing in TEST CRICKET, is GREATER than any wonderfully skillful T20 innings. Youngsters – look, learn & listen!”

https://twitter.com/KP24/status/1080695094607597568?ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw%7Ctwcamp%5Etweetembed%7Ctwterm%5E1080695094607597568&ref_url=https%3A%2F%2Findianexpress.com%2Farticle%2Fsports%2Fcricket%2Fi-saw-the-making-of-cheteshwar-pujara-5535781%2F

They were looking, learning and listening. India’s brightest young batsman Shubman Gill, 19, on the sidelines of a Ranji game, was to say that Pujara’s 500 plus runs was certainly a good performance but it was the 1,200 plus balls he faced that set a new benchmark for youngsters like him. The Instagram generation was finding Pujara lit. Over-fed with T20 cricket, where they tried to find their batting heroes, they were now understanding the science of Test match batting.

The journey from the neem tree to being Test cricket’s Big Banyan hasn’t been easy. Social media has reduced the word “journey” to the most cliched platitude used to describe everything from a Roadies eviction to completing reading a paperback. But in Cheteshwar’s case, it is justified. His 30 years have the necessary gravitas to be called a journey.

To understand the quantum of Pujara’s achievement and to calibrate his leap from cricket’s outpost to the fulcrum of India’s batting in the historic series in Australia, one needs to first understand Kothi Compound of Cheteshwar’s growing years.

Like most Railway townships, this one too was deeply steeped in official hierarchy. Subtle segregation stared at you from every corner. Once the regional headquarters of the British East India company, Kothi Compound had a very noticeable Raj hangover. The sahebs with their army for retinues still ruled from high-ceiling offices in colonial buildings that had front gardens with Victorian fountains.

Watch | Express Adda with Cheteshwar Pujara

The sahebs’ homes were called bungalows, the staff lived in ‘quarters’. The Grade A officers called their watering hole the ‘Club’, while the sports and recreation place for the rest was the less fancy and more crowded ‘Institute’. The officers and their families did enter the Institute to watch those monthly movies on the 35mm screen mounted on the wall of the badminton court but they sat on chairs in the viewing gallery above. The others, meanwhile, would dutifully squat on the wooden floor.

Sports was big. Everyone played something. It could get you a sports quota Railway job, in many cases like their father or mother. You just needed to be half-decent at a sport and the rest got managed. Someone always knew someone who had dutifully served one of the ‘recruitment sahebs’ who was obliged enough to put in a word to the ‘badaa saheb‘ and get him to sign on the sports quota appointment letter.

There were some ‘quarters’ that had become almost ancestor homes of families as they got passed from grandfather to father to son. Kothi Compound was a cocoon no one wanted to leave. Status quo was everyone’s ultimate aspirational goal.

Actually, not everyone. A couple of Kothi Compound kids from the ‘quarters’ worked hard to earn wings. They flew far from their cosy nests to be the champions of their field of pursuit. They would go on to build much bigger bungalows which even the sahebs couldn’t dream of owning.

Arvind lives in one such home these days. However, back in the day, he was a senior clerk in the engineering department from the quarters. He was different, an outspoken outlier.

A student leader of repute, he was as popular as the other prominent figure on the campus — the present Gujarat CM Vijay Rupani. He had regular run-ins with the sahebs because of his frequent absence from work — first when he was player and later when he got into coaching Cheteshwar.

These days he often laughs recalling those rebellious office days. He once got a local MP to write a letter to the Railway Minister when he didn’t get an increment that he thought he deserved.

This other time when a twisted officer called him a liability to the Railways since he was mostly not at work, Arvind reminded him of his corrupt ways and called him a bigger burden for the employers. “He didn’t bother me after that,” he says. Pujara Sr could afford to be a rebel, because he wasn’t looking for favour from sahebs — a railway sports quota job or a quarter for his son. He had bigger dreams.

So did one of his other colleagues, a draftsman in the railways engineering department, whose home was barely a 2 minute walk from where he lived. They were the Sikkas, a family of four with two academically brilliant, gifted kids. One of them was Vishal, whose sparkling mark sheet was the reason for the sound thrashing the neighbourhood kids received on the day when the report card landed at home. “Seekho kuch Sikka saab ke ladkon se“, the mothers would berate. A few years back when Vishal Sikka became the Infosys CEO and MD, old-timers at Kothi Compound weren’t surprised. It was the same when Chintu made it to the Test team. They knew these kids were different.

The myth built around Pujara in Kothi Compound has a refreshing novelty. There are no neighbours talking about shattered window panes or PE teachers to bore you to death with a tale of talent-spotting skills. That’s because Cheteshwar never played gully cricket and his father decided his son’s career path even before he got to school.

It wasn’t just about playing cricket, it was about playing it correctly. Unlike many child prodigies with pushy parents who get burnt out or bored with time, Cheteshwar too fell in love with batting. The Pujaras at the Railway ground, they were as permanent as the neem tree near the volleyball court. Be it morning, afternoon, evening, summer, winter, monsoon; Cheteshwar kept hitting the ball straight.

A young Cheteshwar Pujara in whites. (File)

The image of the kid in whites with light eyes and angelic face stayed with me even when I left Rajkot for my first job, reporting on sports for The Indian Express in Ahmedabad. I kept hearing about Cheteshwar’s rise from friends and family. Our house-help’s son, Sultan, who had showed early promise as a swing bowler, had joined the Pujara nets. Arvind didn’t charge the kids any fees, all he needed was discipline and a promise that they would never play tennis ball cricket. Pujara Sr still looks at amateur cricket with the kind of disdain that Gods reserve for atheists.

Arvind would throw the new ball to Sultan when Cheteshwar padded up. Sultan would update me about Cheteshwar’s sturdy defence and even joke about his insatiable hunger for batting. “Bhaiya, bilkul Dravid jaisa khelta hai, out hi nahi hota”. Even today I occasionally remember Sultan on hearing international bowlers express their helplessness at press conferences on days Pujara is in the zone. During one of my regular visits home at Rajkot, I walked to the railway ground with a friend. We met Arvind, he spoke about the hardships of raising a young cricketer, his recent PF withdrawal to buy new cricket balls and how Cheteshwar at 13 had made it to the Rajkot u-16 team.

Over the years, whenever I called Arvind to talk about a Cheteshwar knock, he would keep going back to those days of struggle. He would invariably mention his wife, who would stitch clothes, save money, wait for a promising IPO, apply and if lucky multiply her meager income. She wanted their son to have the best. “I had a modest salary and I don’t know how she managed but Chintu would have dry fruits before leaving for training and coconut water on return,” Arvind would say.

In early 2000s, one evening, while I was scanning the wires in office, I got a call. Arvind was excited, Cheteshwar had scored a 300 in a u-16 game. We got talking, he revealed how at one point he had thought that his son might have to give the game a miss. The story goes that Arvind had gone to Cheteshwar’s school to borrow the team bat but the PE teacher wasn’t obliging. He didn’t have the money to buy a new bat. It was only after a bitter fight, the angry father walked out of the school with the bat. He was getting frustrated, the inability of the system to support a genuine sporting talent was testing his patience.

The story of the borrowed bat has an interesting sequel. More than a decade later, in 2017, I had gone to Rajkot to cover the assembly elections. I called Arvind, we met. I had with me a friend who was part of our tennis group and was now a school teacher. Arvind was unusually tongue-tied that day. Later that evening, I would get a call from him, he told me that the friend accompanying me was the PE teacher who had tried his best to deny Cheteshwar the bat with which he had scored that 300 at 13. There are some wounds that even time can’t heal.

Despite the 300, Cheteshwar wasn’t picked for the India u-16 Asia Cup squad. He is too slow, was the explanation. The Strike Rate ghost has chased him since he was 13. It didn’t bother him then, it hasn’t bothered him now.

The Strike Rate ghost has chased him since he was 13. It didn’t bother him then, it hasn’t bothered him now. (Express Photo by Kevin D’Souza)

There was also an attempt to change his grip. While attending a national junior camp as a teenager in Mumbai, he was told by a coach that he held the bat way too low. A worried Cheteshwar would call his father, who would ask him to follow the coach’s order, but only when he was looking. Once he was gone, he told the confused boy, he should switch back to the original grip.

Go back to any of his innings and watch how Cheteshwar gets ready to take on bowlers. Before virtually every ball he faces, he raises the bat to his chest, ensures that his right hand is strangling the neck of the bat and the left is just above it. He seems obsessed, to get that distinctly bottom-handed grip to exactly where he, and his father, want it to be. The world had doubts about Cheteshwar’s batting but the Pujaras were sure. They were stubborn but they seemed to know what they were doing. The world has taken its own sweet time to come around. Phew, it took a couple of decades to have a consensus on Cheteshwar, the Test player.

There have been a few times when Arvind has sounded shaken. Once in the mid-2000s, he called to ask if I knew some charity organisation that funded cancer treatment. It was an inquiry for his ailing wife. She would lose the battle. Arvind was shattered. Just when his doubters were increasing, he had lost his biggest backer.

Once when I went to their new sprawling home that has a lift and mini-garden on the first floor to interview the father and son, Arvind got emotional while having lunch. He said that the poky kitchen at their Railway quarters might have been too stuffy but the food that his wife cooked there is best he had ever eaten.

A heart patient, Arvind has been on an emotional rollercoaster following his son’s career. Those long periods when Cheteshwar was recovering from surgery or the days when he was intriguingly dropped from the playing XI were tough on the 68-year-old.

He once told me about that one wish he has. “Several times during nets, I have seen him bat flawlessly. It’s quality batting and a treat to watch. I just want the world to see him bat like that,” he said. In Australia, the world got that privilege. I called him to say that the commentators were saying that the rest of the Indian batsmen should learn the art of Test match batting from Cheteshwar. He chuckled on the phone but didn’t say anything. Finally, after scoring 5,000-plus Test runs, the wise men with a mike in hand were changing their opinion. Those folded hand emojis in the tweets of fair weather pundits looked like apologies not salutations.

Finally, after scoring 5,000-plus Test runs, the wise men with a mike in hand were changing their opinion. (AP Photo)

There was someone who saw the spark in Cheteshwar very early. That was the time many tried to dismiss the boy from Saurashtra, who was in a habit of scoring tons for hundreds on the rather sluggish tracks at Rajkot. Flat-pitch bully was a term often used by former cricketers, and even journalists, from Indian cricket’s traditional cricketing hubs.

Cheteshwar was in Bangalore playing for his long-time employers, Indian Oil Company, in a corporate tournament. As usual he was scoring heavily. He had scored a couple of hundreds and was nearing the third. That’s when Rahul Dravid, the then India captain, turned up at the ground for a jog. The batsman on the centre square made him curious. He asked the scorer. True to his profession he also gave the run details of the boy who would go on to fill Dravid’s shoes as India’s reliable No.3.

It was a Saurashtra Cricket Association official who told Arvind about this. “From the stadium, he called Niranjanbhai (BCCI old hand and SCA secretary). He told him ‘take care of this boy’,” recalls Arvind. Later when Dravid came to Rajkot for a Ranji game, he would meet Cheteshwar again. Standing in the slips, he had a closer and longer look at the Saurashtra No.5.“ After the game, he called the Saurashtra captain and told him that Cheteshwar should bat up the order. This shows his class,” says Arvind. Years later, Pujara would make his Test debut and he would bat at No. 5 behind Dravid and Tendulkar.

“Take care of this boy,” Rahul Dravid, who was India captain then, had told SCA secretary Neeranjan Shah after seeing a young Cheteshwar bat in Bangalore. (Express Archive)

I first got a glimpse of that rare show of chanceless batsmanship in 2006, when I went to Sri Lanka to cover the u-19 World Cup. Cheteshwar finished as the top run-getter. A dear old friend, veteran cricket writer Trevor Chesterfield, a South African of New Zealand origin who had settled in Sri Lanka, too had dropped by at the ground. Pointing to Cheteshwar, he asked me, “How’s that boy? He reminds me of Barry Richards.” “Seriously? Chesters?,” I asked. “I have seen the world, I know,” he replied. I shared the conversation with Arvind, he was over the moon. Early last year, I was in Cape Town watching India play South Africa and the locals compared him to Barry Richards again. Those were early signs that 2018 was looking like Cheteshwar’s breakout year.

Over the years, I have had a chance to see Cheteshwar bat live in India, Sri Lanka, England and South Africa. Around the world, sitting in press boxes, that tower over the sightscreen and watching that Railway kid with light eyes and angelic face, I have been reminded of my wonderland and 3, Kothi Compound. I keep hearing that Cheteshwar’s unusual batting approach, grows on you. Certainly not for someone who has seen Cheteshwar grow.