Written by Shivani Naik | Mumbai | Updated: May 8, 2018 8:52:11 am

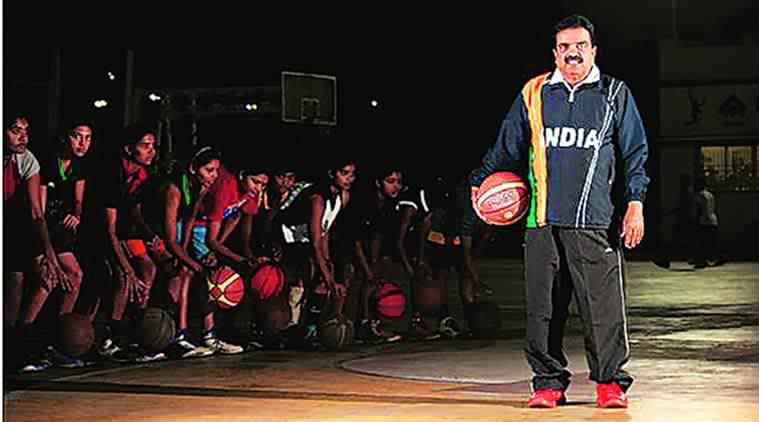

Thank you for reading this post, don't forget to subscribe!Rajesh Patel (62) breathed basketball and died trying to steer the latest generation of hungry, driven hoopsters from Chhattisgarh. Rajesh Patel, who passed away on Monday, was instrumental in the comeuppance of basketball players from Chhattisgarh.

“Bandook ki goli ki tarah bhaago. Tumhe koi rok nai paega!”

Anju Lakra was barely 5’2″, and hoping to take on India’s best basketball player almost a foot taller than her. Coach Rajesh Patel of Chhattisgarh told her what he was to drill into at least 100 other girls—tall, short, strong or frail. “He took the height out of the equation. He said you need only two things to win a fight —speed and defense. Run and shoot like a bullet, he would say,” Lakra recalls.

She’d been a fringe handball player in her school in Bhilai, when Patel, impressed with her natural speed, steered her towards basketball. “Most of us were tribal girls who suffered from malnutrition and didn’t look anything like athletes. I belong to a scheduled tribe, but Patel sir ensured that I became a high-ranking railway officer, a TT, on the basis of my basketball. He really saw no limitations in anyone—of physique or background,” says the former India international, known for her lightening runs taking on the tallest and mightiest even while driving-in. “He helped us break free,” she added.

Patel (62) breathed basketball and died trying to steer the latest generation of hungry, driven hoopsters from Chhattisgarh. On his way to Ludhiana for the ongoing junior national championships, Patel suffered a cardiac arrest at Panipat—which proved to be fatal, a year after he’d been felled by a stroke. He had been suffering from kidney issues and was a diabetic. Chhattisgarh twice reached the Senior National finals, winning famously against Railways, and regularly contributed to the Indian squads, with players coached and mentored by Patel standing out for their speed and tight grasp of fundamentals.

Screaming “defense, defense” through the match was a duty assigned to two team members for the duration of the match, as the NIS coach stressed on what is a fulcrum of all succesful teams, especially those without the vertical advantage. His wife, who took over the responsibility of looking after two dozens of girls at the Bhilai residential academy (top floor of the Patel household), was known to carry a few pieces of cloves with her, simply to preserve his voice, as he boomed out instructions, screaming hoarse.

India international Seema Singh was taller, but knock-kneed when she started out. Doctors had told the reed-thin girl, when she was 11, that she would never be able to play a sport. Patel took it upon himself to first strengthen her body, and then sculpted her game into one that was good enough to make the India team, and more importantly beat the country’s most domineering unit, Railways at the Senior Nationals.

“I’d cried after doctors told me that. Sir made me run on sand. He made me eat properly. From struggling for two square meals to travelling abroad, from being nothing to a respected railway TT with several promotions only because of basketball, he changed everything,” she says, adding, “Life would’ve stayed plain—nothing exceptional. He gave us confidence, and this was when Chhattisgarh was just born as a state.”

Patel had been a player himself taken on sports quota at Bhilai steel Plant in 1979, but held back by his 5’5” modest frame. When he started coaching —devoting 16 hours to the academy he helped build—he decided that he would build a strong team, never mind that it was tough to get parents on board. When he saw blitzy speed in a player, he would go about convincing the parents to allow their daughters to get into the sport. Seema and Akanksha Singh’s father, a CISF constable, would be prevailed upon to let his daughters stay on in Bhilai while he was transferred.