Sandeep Dwivedi writes: They have all looked the bull in the eyes and said, ‘What’s pain?’

Thank you for reading this post, don't forget to subscribe!Shared News: June 8, 2022 8:51:01 am

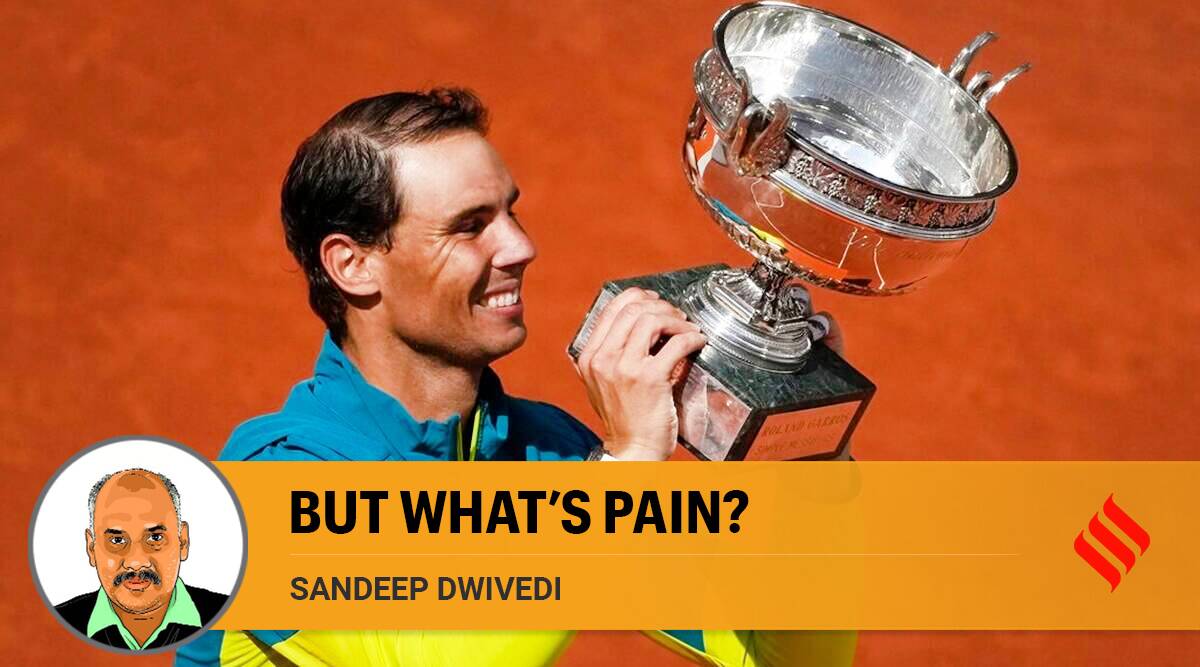

Spain’s Rafael Nadal holds the trophy after winning the final match against Norway’s Casper Ruud in three sets, 6-3, 6-3, 6-0, at the French Open tennis tournament in Roland Garros stadium in Paris, France. (AP)

But for a singular moment while on the train to Oxford for an important athletic meet, Roger Bannister had a rather uninspiring start to what eventually would be the most memorable day of his life. It would get marked forever as a seminal date in track and field history, some would also consider it a milestone run that redefined the limits of human endeavour.

The story goes that on May 6, 1954, the amateur runner and full-time medical student from London had his usual breakfast of warm porridge, attended to patients in the OPD, sharpened his spikes on the grindstone at the hospital lab and, after his shift, joined the crowd of daily commuters at Paddington tube station.

Bannister, 25 then, had plans to give his all over a mile that evening. For the athlete keen to pursue advanced neurology, this was to be his final shot at breaking the 4-minute barrier. The weather, however, was in no mood to make it easier for him.

With the winds howling and rain drops getting larger, Bannister, while on the train, was tempted to postpone his attempt at making history. It was then that his Aussie coach Franz Stampfl cleared his clouded mind. “If there is only a half-good chance, you may never forgive yourself for missing it,” he said before uttering the magical words that would ring through time. “You will feel pain, but what’s pain?”

For a species that is wired to chase comforts and spends most of its waking hours thinking of ways to make life easy, Stampfl’s matter-of-fact dismissal of physical suffering, a cold handshake with pain, sounds unreal. It’s an emotion alien to the majority — the mortals inclined to wince much before the pin-prick of the vaccination needle, pop pain-killers to deal with a minor sprain and fuss over a honeybee sting.

Away from the world of the mollycoddled, are sporting arenas, the home of hardened men and women. Their idea of a satisfying day of training would mean coughing blood after a workout and getting dizzy with pain in the limbs. On top of their pyramid are those with higher pain-thresholds and the capacity to keep returning to these torture chambers with unbridled enthusiasm. They are those for whom life is an unending 24-hour cycle of first getting their bodies battered and recovering in time to get battered. All done willingly, with gusto. While on this punishing schedule, they log those proverbial 10,000 hours to be masters of their craft and get hailed as gifted geniuses by the world.

Men like Rafael Nadal, Sachin Tendulkar, Diego Maradona haven’t let fragile ligaments, damaged elbow and mangled ankle — all tear-inducing painful, career-threatening setbacks — downsize their ambitions. They have all looked the bull in the eyes and said, “What’s pain?”

When just 18, Nadal was told that he had an inherent weakness, his ligaments weren’t strong enough to hold his ankle. It was a heart-breaking diagnosis. It was something that couldn’t be rectified, the young Spainard would have to manage pain all his life. There were those who advised him to tone down the physicality of his tennis. Nadal doesn’t glide around the court like a Roger Federer. His is the “scampering on the baseline” hustle and he wasn’t giving up on the only way he played the game. Legends of the game are too sure about themselves, they don’t listen to advice easily, even if it’s the medical kind.

Till date, Nadal’s calling card remains the relentless pursuit of the ball. Fourteen French titles means he has run the full course on the toughest Slam several times over. It was said that the weak ligaments would cause excruciating pain, or get snapped, because of the twists, turns and torque the red clay puts on the ankle. Roland Garros is no posh serve-and-volley Wimbledon-like affair. It’s the working man’s Slam: No sweat, no silverware.

Nadal’s quarter-final against Djokovic this year started on Friday and ended on Saturday. Before the tournament he had spoken about pain, at the end of it, he shared how he dealt with it. He numbed his ankle, risked damage to ligaments — all to be on the podium alone and bite the wings of the sparkling bowl.

In a recent interview to The Indian Express, Tendulkar had spoken about pain and the phase of his career when he was operated virtually every year. “In 2003, I had a left finger injury, In 2004, I had the tennis elbow and had an operation in 2005. Around 2006-07, shoulder and right bicep also needed to be operated upon. I also had a couple of groin surgeries. Then, there was another wrist surgery later in my career.” The elbow recovery was most painful. Tendulkar said he couldn’t lift a coffee mug. If locked in a room, he couldn’t turn the knob. Holding his extra heavy bat was out of the question.

That Tendulkar expression of helplessness when he hit rock bottom could be seen on Maradona’s face when he got injured or was brought down after a rough tackle. The Asif Kapadia docu-feature film on the greatest footballer ever has a private moment of despair.

It’s from Maradona’s days at Napoli, where his backers, underworld bosses and dodgy owners, wanted him on the field for every match at any cost. He’s lying on a doctor’s table with face down, and a pair of amateur hands are drilling holes with a micro-slim long needle on his back. Maradona writhes in pain, but says that the agony is a little less than last time. The man with the needles says, without any guilt, last time it was without anesthesia. In the background, his wife Claudia Villafane, says, “He would get five different injections in different places, and he would play the next day. Diego would bite the pillow because of pain.” Cut to Maradona’s face, who lets out a heart-breaking groan.

Before that, while at Barcelona, he had got caught in a diabolical lunge from a defender called Andoni Goikoetxea aka Butcher of Bilbao. Of his trauma, Maradona would say, the blow to the ankle was followed by a sound “like a piece of wood splitting”.

Like a true friend, in thick and thin, pain accompanies those driven to succeed.

Go back to the iconic frame of Bannister breasting the tape to check the coach Stampfl’s pain prognosis. If pain had a face, the photographer had captured it beautifully. The English runner’s lungs seem to have given up, the mind looks tired asking the limbs to stop. Bannister’s body on that rainy summer evening stayed stubborn, it kept flying towards the finish line.

He would later say that the final few seconds seemed like an eternity. Bannister was conscious that in case the clock would win the race, there would be no arm to hold him beyond the finish line and “the world would seem a cold, forbidding place.” His final leap for the line was to save himself from being remembered as an also-ran, a valiant trier and a sorry figure. The effort took its toll.

“I collapsed, almost unconscious, with an arm on either side of me. It was only then that real pain overtook me … I felt like an exploded flashbulb,” was Bannister’s recollection of his euphoric moment. It could well be Rafa sprawled on red clay.

Science says that pain has the power to enhance pleasure. Experts talk about a phenomenon called “the runner’s high” — the pleasant feeling of lightheadedness after an exhaustive workout. It’s attributed to the flow of opioids, a chemical triggered by the body when it experiences pain.

It’s that heady feeling only the greats would have experienced. As for the mortals and the mollycoddled, for want of a better parallel, it’s like the beer tasting better after a long hard day or a shikanji being sweeter after being out in the sun.