Sreejesh plays a sport not too popular in his home state, but has endeared himself to them with his prowess & personality. This is the story of the goalkeeper who made the most vital save of his career, repelling Germany’s penalty corner to ensure India’s podium finish at Olympics after 41 years.

Thank you for reading this post, don't forget to subscribe!Shared News: August 5, 2021 1:16:35 pm

PR Sreejesh poses for pictures as he celebrates winning the match for bronze. (REUTERS/Bernadett Szabo)

When PR Sreejesh was in primary school, at a village 30 kilometres east of Kochi, his physical education teacher was convinced that he had unearthed the next sporting sensation. Sreejesh was good at everything — he could hurl the discus and javelin a fair distance, he could leap, smash and spike, he was in both volleyball and basketball teams, could perform the long jump as well as high jump. Sometimes, he could run too, though he himself despised running.

He revelled in every sport, expect hockey that is.

So versatile was Sreejesh that he was referred to GV Raja Sports School, the government-run primary sports school in the state capital Thiruvananthapuram, where he could hone whatever sporting skill he wanted.

It was difficult to convince his sceptical parents, who were farmers, before his teachers dangled the golden carrot of those times. “Sports quota, government job.” Sreejesh too was gung-ho, except when the moment of departure arrived, an ineffable heaviness weighed his mind down. “I had never stayed away from them, and the day I was to board the train, I broke down. I didn’t want to leave. I am usually a confident boy, but that day, I felt uneasy,” he had once recollected to this reporter.

PR Sreejesh with coach Graham Reid and skipper Manpreet Singh after the historic win against Germany. Thiruvananthapuram, just 200km away, seemed like eons away. An unfamiliar culture, food habits and surroundings, a faraway universe from his family, friends and farms. But as the train chugged along the lovely backwaters and rivulets on that scenic route, Sreejesh rearranged his morale. At the end of the three-hour-journey, as he set foot in Thiruvananthapuram, he suddenly felt grown-up and confident, and ready to face the world. “I felt a sudden wave of confidence, as if my life was going to change, that this was the beginning of my real journey,” he said. A new beginning Life was to change beyond Sreejesh’s wildest imagination. At the school, he passed by a group of teenagers playing hockey. He had little clue that this was to be his destiny. The next day, he walked into the throws arena. He was left shocked by the physicality of fellow trainees. “I felt like a worm.” He stopped by the basketball and volleyball courts. “I seemed like a dwarf.” He deliberated on football. “No, it involved a lot of running”. Cricket? “No, I didn’t get the kicks.” Finally, he made friends with a couple of hockey guys who were his age and of similar physiques. He used to hang around with them and would sometimes wield the stick, but without much success.

Let me smile now 🙏 pic.twitter.com/8tYTZEyakU

— sreejesh p r (@16Sreejesh) August 5, 2021

That’s when one of the hockey coaches, Jayakumar, spotted him. “He was a defender or a centre-half, who was a lazy runner. But had excellent reflexes that always saved him. Then I thought why not make him a goalkeeper. Kids don’t like being ’keepers, but it’s an important role,” he explains. Years later, those split-second reflexes would make him one of India’s finest goalkeepers. His saves throughout the Games were instrumental in orchestrating India’s bronze medal in Tokyo, ending a 41-year-drought. The saves against Germany were spectacular, especially the one he pulled off in the dying stages of the match, locked at 5-4. The penalty corner looked goal-bound before his reflexes intervened. It was not reflexes alone that went behind the save, but his unfettered passion, his unbudging will.

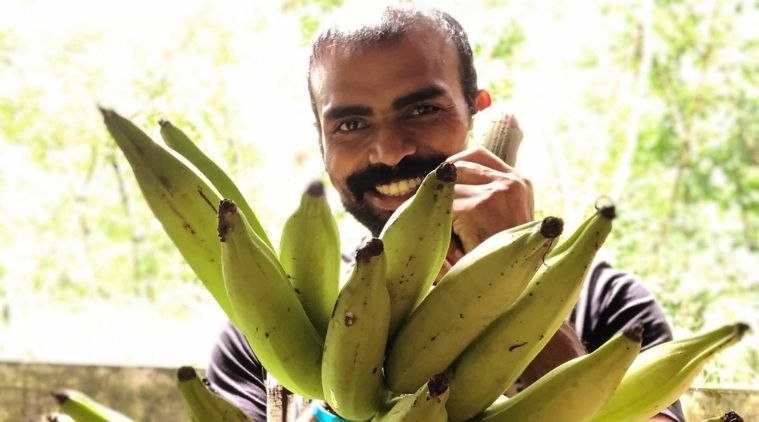

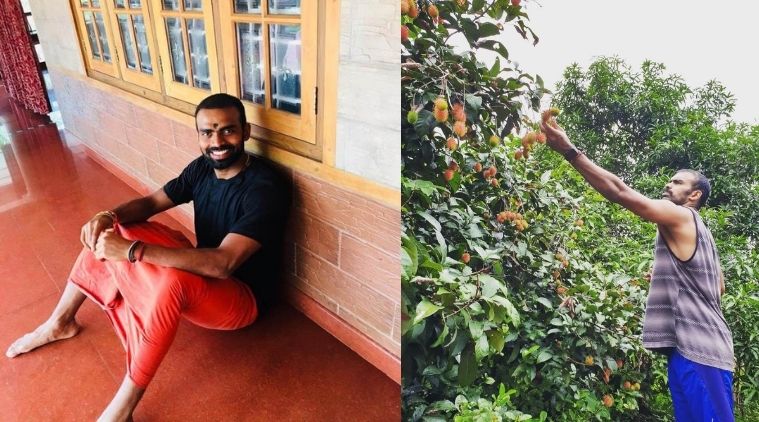

PR Sreejesh at his hometown. (Express Photo)

After the game, India coach Graham Reid said, “Having someone in goal as reliable as Sreejesh helps. He’s a stalwart of Indian hockey. He’s done a lot of work in the background to get to where he is today.” To be the stalwart, it needed hours on field. “He took time to get used to the gear, but everything else he learned fast. He had that game sense and anticipation, and for his age, he had the presence,” Jayakumar says. Then as Sreejesh hit teenage, he started growing taller and muscular and was actually mistaken for a shot-putter or javelin thrower. “A lot of people thought he was one of them,” he says. Though Jayakumar was certain of his ward’s potential, he knew his potential would be wasted in Kerala, a hockey backwater, where hockey is that game “where India was once glorious but now reeling”, barely watched even during the Olympics. Ask a Malayali how many players he knows. Most likely, he would roll down three fingers. Dhyan Chand, Dhanraj Pillay… and now Sreejesh. No takers for hockey That the state built its first astro turf in 2015 nails the anonymity of the game in this neck of the woods. Just seven have represented the country from the state, and except Sreejesh all in the pre-astro turf era. He had just a ragged goalkeeping gear, and worse, it was not even available in his town. Coincidentally, though, the state’s two most reputed hockey players were goalkeepers — Helen Mary (2002 Commonwealth Games gold medallist) and Manuel Frederick (1972 Munich Games bronze medallist). Like the baseball club in Hindi movies, the hockey stick was that clawed piece of wood bad guys brandished in movies. So Jayakumar called one of his friends, then national junior coach Harendra Singh to check out the youngster. The latter, coincidentally, had come to watch a U-14 tournament in Thiruvananthapuram. Impressed, he invited Jayakumar and Sreejesh to the junior camp in Delhi in 2003. The latter reached Delhi with just a non-branded bag and not even a ’keeper’s kit as his parents could not afford one (it used to cost around Rs 15,000). “In inter-state tournaments, they used to make fun of my gear. It didn’t bother me. I had my body and my biggest weapon was my mind,” he had said.

PR Sreejesh at his Kochi residence. (Express Photos)

Wowed by the youngster’s abilities, Harendra took him to the junior camp for the 2004 Asia Cup. He did not make the final squad, but made it to the Junior Asia Cup, after which he was never dropped from the junior team. “Life changed,” Sreejesh said. And it kept changing; he became a multiple-time Olympian, World-Cupper, Asian Games gold medallist, and now Olympics bronze medallist. A beatifically-smiling Sreejesh peers from the oddest of advertisement hoardings, a hair-weaving company’s billboard on one of the busiest roads in Kochi, of a local mattress, a footwear brand that specialises in sandals and slippers, and as a Tokyo Olympics columnist for a vernacular newspaper. Kerala didn’t fall in love with him at first sight, it was more of an arranged marriage, wherein they eventually fell in love with him. Hockey as such has sparse following, leave alone appreciation – Chak De! India barely saw a fortnight. That he repeatedly turned out for Tamil Nadu, as he was an Indian Overseas Bank employee based in Chennai, didn’t foster much love either. Sreejesh could understand this at that time. “It’s difficult to love a goalkeeper. He is invisible, and is only in the limelight when he makes a blunder. When I was young, I didn’t know who India’s goalkeeper was then. Besides, I am not someone who goes behind attention, never gone behind superstar-dom,” he said. Common man becomes icon Not for long though. The sports-mad state desperately needed a sporting hero/heroine. No footballer of IM Vijayan class had emerged since his farewell; no one of the Anju Bobby George mettle either; none after Jimmy George and Tom Joseph in volleyball; Sreesanth, well, was in a whirlpool of mess; Sanju Samson was the perennial, fragrant bud that never blossomed. The Indian Super League had not yet descended and the Indian Premier League no longer had a local team. Then came the barrel-chested Sreejesh with his twinkling reflexes and bullet-proof heart. The 2014 Asian Games gold medal certainly helped build his stature, but it was not merely sporting accomplishments that made him an icon. His demeanour too played a huge role. In image-building, he didn’t need PR machinery. His genuineness endeared, striking an inviolable chord with the masses. He was their ideal sporting hero – a complex concept, as they would adore Maradona, but would not want one of their own to be a Maradona off the pitch. Sreejesh never spun a scandal, was utmost gamely, remained grounded, never threw celebrity tantrums, never ripped off in luxury cars or flaunted monstrous houses (that ubiquitous Malayali fetish), never plunged into ill-advised business ventures. He spoke, talked and walked like an everyman one sees on the street.

Sreejesh sits on top of the goalpost as he celebrates winning the match for bronze. (REUTERS/Hamad I Mohammed)

A tattoo on his right bicep perhaps is his only signage of uberness. He embodied the son-of-the-soil spirit that every Malayali secretly prizes close to one’s heart. Nothing has changed in him. Sreejesh himself had said that a more comfortable home than his netted cage is the verandah of his house, where he could sprawl after a heavy lunch and slip into an afternoon siesta. Last year, he was spotted cleaning the unkempt lane in front of his house in a shirt and lungi with a handloom towel wrapped around his forehead; the video went viral. To curious onlookers, he gently replied: “Who else would wash the dirt that has accumulated in front of my house?”

In television shows, he barely utters a word in anger, his slang unstained by affectations, still permeating the innocence of the countryside. Like Vijayan, he is relatable and approachable, down to earth, and doesn’t entice the hidden tall-poppy syndrome.

“He remains very humble to the day, did not get dragged into a luxurious life. He is a role model for young sportsmen,” says Jayakumar. And he has got an entire state hooked to the unfamiliar rhymes and rhythms of a game that they have never embraced or welcomed.

That, perhaps, is the biggest legacy of Sreejesh — he made football-loving, volleyball-playing, cricket-watching Malayalis watch hockey, follow the game that’s not their first love (or second or third). A journey that began from a sleepy Kochi suburb has waltzed into the collective Malayali sports consciousness.